Along with the adjoining Hagia Sophia, Topkapi Palace Museum, one of the world’s richest museums, might be regarded the best and most visited sights in Istanbul. It is a majestic oriental palace and one of the world’s greatest architectural marvels, located on a triangular promontory dominating the Bosphorus and Golden Horn.

History of Topkapi Palace

The Ottoman sultans’ palace as well as the Empire’s administrative and educational headquarters was Topkapi Palace. The palace was built by Fatih Sultan Mehmed, who conquered Istanbul in 1453, atop the Byzantine acropolis on Sarayburnu, at the extremity of the historical peninsula, between 1460 and 1478.

For almost 350 years, until the early 1850s, Topkapi Palace was the residence of the Ottoman sultans. Sultans relocated to the Dolmabahce Palace in Besiktas, on the Bosphorus coasts, because the palace had become insufficient for purposes such as ceremonies and customs.

Despite the relocation, numerous collections such as the royal treasury, the Prophet Muhammad’s Holy Relics, and the imperial archives remained at the Topkapi Palace. With the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1924, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk ordered Topkapi Palace to be transformed into a museum.

Things to See in Topkapi Palace Museum

The original arrangement of Mehmed’s palace, which comprised of four courtyards connected by high walls, has been preserved. Each courtyard served a distinct purpose and was divided by a gate that gradually restricted access, culminating in the most secluded third and fourth courtyards. The palace’s remaining structures are mostly modest, one- to two-story constructions that have changed roles over the centuries, thus some structures, especially in the harem, aren’t always evident in their role.

First Court

Enter the First Court, also renowned as the Janissaries’ Court or the Parade Court, through the Imperial Gate. The Hagia Eirene, also referred as Aya rini, is a Byzantine church to your left.

Second Court

The Salutation Gate leads to the palace’s second courtyard, also known as Divan Square, which served as the administrative centre. The venue was only open to formal visitors and members of the court. In the Domed Chamber, Council members gathered several times a week to discuss state affairs (sometimes called Council Hall).

State meetings were led by the grand vizier (chief minister), and the sultan listened in from a tiny room within the neighbouring Tower of Justice, the palace’s tallest building, through a guarded window. The sultan could not be seen by the council members, however they would have been aware of his likely presence. The sultan could see the entire palace from the tower’s Neoclassical lantern, which served as a reminder of the sultan’s omnipresence not only in the court but also in the building’s daily life.

The royal kitchens and confectionaries, which now house the imperial porcelain collection, as well as the External Treasury, which houses the imperial armaments, were all located in the second courtyard. The pieces in these collections, like those in the Topkap Palace Museum, were either produced by workshops on the Sultan’s orders, acquired at markets, received as presents from foreign dignitaries, or amassed from defeated people. The porcelain collection, which includes pieces from China and Japan, demonstrates the empire’s vast reach.

Third Court

The Gate of Felicity leads into the Third Court. White eunuchs staffed and guarded the sultan’s personal domain. The Audience Chamber, which was built in the 16th century but restored in the 18th, is located inside. Important government officials and foreign diplomats were escorted to this small kiosk to transact state business. As the ambassadors proceeded through the entryway on the left, the sultan, reclining on a large couch, reviewed their gifts and offerings. The lovely Library of Ahmet III, erected in 1719, is located directly behind the Audience Chamber.

The Dormitory of the Expeditionary Force, located on the eastern end of the Third Court, was closed for renovation at the time of research. When it reopens, it will hold the palace’s extensive collection of silver and gold-threaded royal robes, kaftans, and uniforms. The Sacred Safekeeping Rooms are located on the other side of the Third Court. Many relics of the Prophet are housed in these halls, which are lavishly adorned with znik tiles. When the sultans resided here, the apartments were only opened once a year, on the 15th day of the holy month of Ramazan, for the royal family to pay tribute to the Prophet’s memory.

The Dormitory of the Privy Chamber, located next to the hallowed Safekeeping Rooms, has an exhibit of portraits of 36 sultans. The highlight is Konstantin Kapidagli’s magnificent painting of Sultan Selim III’s Enthronement Ceremony (1789).

Fourth Court

The third courtyard leads to the fourth courtyard, which features tiered gardens and pavilions. It houses the Circumcision Chamber, Baghdad Pavilion, and Yerevan Pavilion, all of which are lavishly ornamented. The quaint gilt-bronze Iftar Pergola, where sultans would break their fast if Ramadan fell in the summer, is one of the most distinctive structures in the fourth courtyard. The fourth courtyard gardens are loaded with tulips, just as they would have been during the Ottoman period.

Topkapi Palace Harem

On the western side of the Second Court, beneath the Tower of Justice, is the entrance to the Harem. If you decide to go – and we strongly advise you to – you’ll need to purchase a separate ticket. When rooms are closed for repair or stabilization, the tourist route through the Harem changes, thus some of the sections described here may not be open during your visit.

The Harem, according to popular belief, was a place where the Sultan might engage in unlimited depravity. This was the imperial family apartments, and every facet of Harem life was dictated by tradition, obligation, and ceremonial. The word harem implies ‘forbidden’ or ‘private’.

In the Harem, the sultans may have as many as 300 concubines, though the number was generally far fewer. The girls would be educated in Islam, Turkish culture and language, as well as the arts of make-up, fashion, comportment, music, reading, writing, embroidery, and dancing once they entered the Harem. They then entered a meritocracy, serving first as ladies-in-waiting to the sultan’s concubines and children, then the valide sultan, and lastly the sultan himself, if they were extremely lovely and talented.

By Islamic law, the sultan was permitted to marry four lawful spouses, each of whom was given the title of kadn (wife). Haseki sultan was the name given to a woman who bore him a son, and haseki kadn to a wife who bore him a daughter. The valide sultan, who frequently possessed enormous landed estates in her own name and managed them through black eunuch servants, ruled the Harem. Her influence on the sultan, his wives and concubines, and state concerns was often deep because she was able to give commands directly to the grand vizier.

The first of the Harem’s 300 apartments were built during the reign of Murat III (r 1574–95); prior sultans’ harems were in the now-demolished Eski Saray (Old Palace), near today’s Beyazt Meydan.

Only one of the six floors of the Harem complex can be visited. The Carriage Gate leads to this location. The Dormitory of the Corps of the Palace Guards, located next to the entrance, is a painstakingly preserved two-story edifice with swaths of superb 16th and 17th-century znik tiles. The Dome with Cupboards, the Harem treasury where financial records were maintained, is located inside the gate. Beyond it is the Hall with the Fountain, which is decorated with excellent 17th-century Kütahya tiles with botanical patterns and Koranic inscriptions and houses a marble horse-mounting block originally used by the sultans. The Mosque of the Black Eunuchs, which is adjacent to this, has Mecca representations.

The Courtyard of the Black Eunuchs, which is similarly adorned with Kütahya tiles, is located beyond this room. The Black Eunuchs’ Dormitories are located beyond the marble column on the left. White eunuchs were used in the beginning, but black eunuchs provided as gifts by the Ottoman governor of Egypt eventually took over. There were as many as 200 people living here, protecting the doors and waiting on the Harem’s women.

The Main Gate into the Harem, as well as a guard room with two massive gilt mirrors, are located at the far end of the courtyard. The Concubines’ Corridor leads to the Courtyard of the Concubines and Sultan’s Consorts on the left from here.

A room with a tiled fireplace is located across the Concubines’ Corridor from the courtyard, followed by the Valide Sultan’s Apartments, the Harem’s power centre. The valide sultan monitored and ruled her vast ‘family’ from these beautiful apartments. The Valide Sultan’s Salon is particularly noteworthy, with its magnificent 19th-century frescoes depicting bucolic vistas of Istanbul and a lovely double hamam dating from 1585; the gilded bronze railings were added later.

A magnificent reception room with a big fireplace goes through the Valide Sultan’s Courtyard to a vestibule decorated in 17th-century Kütahya and znik tiles. Before entering the opulent Imperial Hall for an audience with the Sultan, the princes, valide sultan, and senior concubines waited here. The hall was constructed during the reign of Murat III and redecorated in baroque style by Osman III (r 1754–57).

The Privy Chamber of Murat III, one of the palace’s most opulent rooms, is close by. Almost all of the decoration, which dates from 1578, is unique and assumed to be Sinan’s work. The rebuilt three-tiered marble fountain was built to provide the sound of flowing water while also making it impossible to listen in on the Sultan’s conversations. Later 18th-century additions include gilded canopied seating spaces.

The Ahmet III Privy Chamber and accompanying dining room, erected in 1705, are right next door. The latter is lined with lacquered oak panels with lacquered depictions of flowers and fruits.

Topkapi Palace Imperial Treasury

Topkap’s Treasury, on the eastern edge of the Third Court, houses an incredible collection of gold, silver, rubies, emeralds, jade, pearls, and diamond-encrusted objects. The structure was built in 1460 during the reign of Mehmet the Conqueror and was originally utilised as reception halls. When we last visited, it was closed for a significant restoration. Look for the jewel-encrusted Süleyman the Magnificent Sword and the remarkable Throne of Ahmed I (called Arife Throne), inlaid with mother-of-pearl and constructed by Sedefhar Mehmet Aa, architect of the Blue Mosque, when it reopens.

Don’t overlook the Treasury’s famed Topkap Dagger, which was featured in Jules Dassin’s 1964 film Topkap as the object of a criminal robbery. Three massive emeralds adorn the hilt, and a watch is set into the pommel. The Kaskç (Spoonmaker’s) Diamond, a teardrop-shaped 86-carat stone surrounded by dozens of lesser stones that was initially worn by Mehmet IV upon his ascension to the throne in 1648, is well worth looking out.

Facts about Topkapi Palace

- The Ottoman Sultans used to live here.

- One of the world’s most valuable museums.

- The best examples of seal, book binding, jewellery, and box craftsmanship, as well as inscriptions, are housed in this museum.

- Between the years of 1460 and 1478, Topkapi Palace museum Istanbul was constructed.

- The world’s finest collection of Chinese porcelain is housed here.

- In 1924, it was turned into a museum.

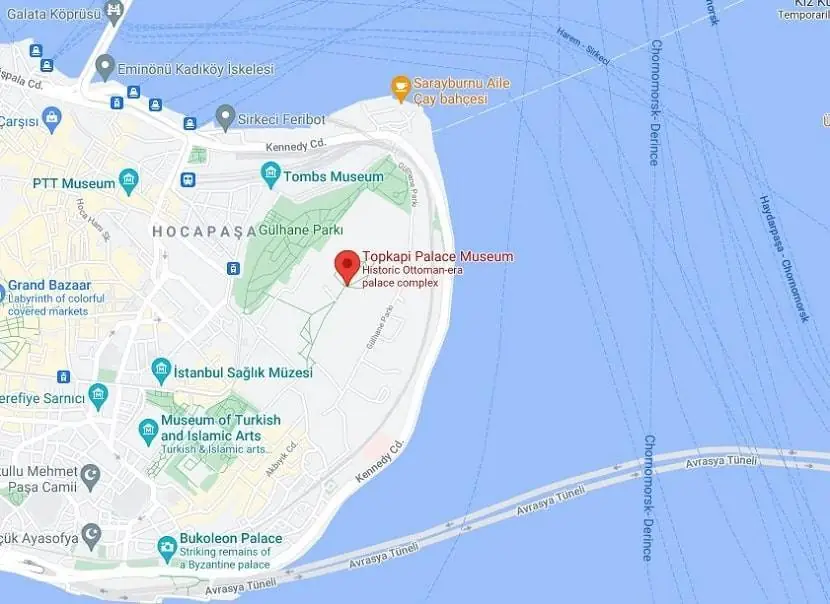

Topkapi Palace Map

Visiting Information

Location: Cankurtaran, 34122 Fatih/İstanbul, Turkey

Opening Hours: 09:00-18:00 (Closed on Tuesdays)

Tickets: You may expect to wait roughly 2 hours for an access ticket, depending on the throng, so arriving at 9:30 a.m. could mean an 11:30 a.m. entrance. As a result, we strongly advise you to purchase your Topkapi Palace tickets online. We suggest getting the Palace tickets between 09:30 and 15:30, since it will be less busy and you will be able to see more of the palace.